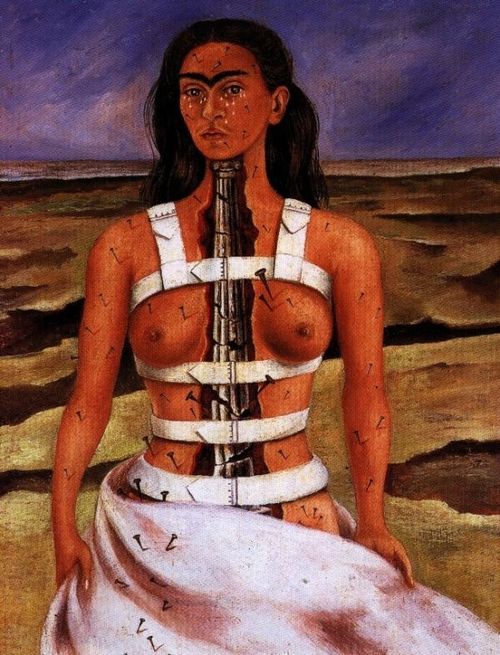

Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column, 1944

Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column, 1944

That [Kahlo] became a world legend is in part due to the fact that … under the new world order, the sharing of pain is one of the essential preconditions for a redefining of dignity and hope. John Berger

Please don’t come back!

My forehead thumped down on my desk after a ten minute appointment that had stretched out to over half an hour, I felt completely exhausted and still I had another 17 patients to see and I was now running 25 minutes late. It wasn’t just that I felt exhausted, I felt useless and demoralized and more than that, I felt angry, really pissed off.

I had spent the last 30 minutes listening to Sharon describe her pains, which shifted from the somatic – how they feel, to despair – how she feels, and anger – how she feels about me. Why didn’t I know what was wrong with her? Why didn’t I refer her for more investigations? Why didn’t I send her to a [another] specialist? Why didn’t I listen? At some point I tried to introduce the idea that perhaps a pain-psychologist might help but this merely ignited the oil I’d been trying to pour on troubled waters. “You don’t even know what’s wrong with me and now you’re trying to tell me it’s all in my head, you’re not listening to me!” she all but screamed at me, tears welling up in her eyes. “No, no, no, not at all!” I actually held my hands up in front of me in self-defence, “but pain, whatever the cause, is always emotional and physical.” I believed what I was saying as I dug myself deeper into a hole I wasn’t going to dig myself out of. She was in fighting form and I was floundering. She took advantage, “You’ve done nothing for me, nothing! I want to see someone else.” I’ve been her doctor for almost 10 years and have seen her health deteriorate dramatically, her marriage take the strain and recover, her children in and out of illness and her husband through his redundancy and depression and more. I’d visited her at home and referred her to rheumatologists, physiotherapists and a pain clinic. I felt like I had nothing else left to offer. Her killer blow left me speechless. “I don’t know what to say,” I admitted, defeated, barely able to maintain eye-contact. She stood up and left.

The sufferer is in a state of high alertness and of anger looking for a cause. What strikes me is that (in my case anyway) anger comes before the pain: a wash of strong, predictive, irritation emotion that I don’t feel at any other time. Hilary Mantel

I’ve had this consultation in various forms too many times to count and I’ve discussed the problems with colleagues enough to know I’m not alone. Why then is it so hard for doctors and patients to cope with chronic pain?

Restitution and chaos

Yet most people who decide to become doctors respond to a deep intuition about life and their own lives. To become a doctor implicitly places us on the side of those who believe that the world can change – that the chains of pain and suffering in the world can be broken. For every medical act challenges the apparent inevitability of the world as it is, and the natural history of illness, disability, and death. Every antibiotic, every surgical intervention, every consultation and diagnosis becomes part of an effort to interfere with the “natural” course of events. Thus, at a profound, even instinctual level – because it precedes rational analysis – people become physicians to find a way to say “no” to disease and pain, and to hopelessness and despair – in short, to place themselves squarely on the side of those who intervene in the present to change the future. Jonathan Mann

This moving statement helps to explain why responding to our patients pain, especially chronic pain for which we emphatically cannot say “no”, is such a challenge. We are naturally solution-focused and the stories doctors like to tell about our work and our patients like to tell about their illnesses is a ‘restitution narrative’ in which illness is overcome and good health restored. We find it difficult to describe alternative narratives and this leaves us and our patients with chronic pain deeply frustrated. Doctors who cannot make their patients better, or even relieve their symptoms, suffer crises of identity and purpose and seek to avoid the situations that make us feel like this. In cancer care, barely 2% of spending is on palliative care and the proportion is even less for other diseases where suffering is at least as unpleasant and prolonged. Doctors have traditionally abdicated responsibility for the relief of suffering to nurses and now we’ve created specialist pain and palliative care services to do this difficult work for us. And yet our patients still come back to us. And then what happens? Instead of restitution we end up with chaos. In a chaos narrative, patients and doctors are stuck. According to medical sociologist Arthur Frank, “people live chaos, but chaos cannot in its purest form be told”, “if medical communications often fail people living in chaos, it is equally true that living in chaos makes it difficult to communicate”. Doctors and patients with chronic pain often find ourselves lost for words as I did with Sharon. This is one reason why we stop talking altogether and resort to questionnaires from which we choose words like burning, aching, sharp, dull, stabbing, gnawing, shooting, throbbing etc. instead of exploring narratives.

Another patient came in to see me, full of anger and frustration. Over and again she said how sick she was of explaining to other people why she couldn’t come out, help out or do the things she used to do. I hardly had a chance to speak, every now and again she challenged me to offer her an investigation or a treatment she hadn’t tried that would relieve her pain or chronic fatigue. I knew her well, but had failed her several times before and she no longer saw me as her usual GP. As gently as I could I asked her to describe why it was such a struggle to explain how she felt and she said that she had given up and how isolated she was. I said that in my experience this was all too common and asked if I could show her something that might help. When I showed her the Kahlo picture (above) she burst into tears.

Chronic pain extends to the limits of language and beyond. This was the first time I’ve tried showing a picture to a patient – and it felt very odd, it’s not in the NICE guidelines for chronic pain, but having researched this essay I was acutely aware of how words often fail. The tension in the room was relieved when words were no longer necessary.

Listening to accounts of pain

Patients’ accounts of pain are valued by doctors for the contribution they make to a diagnosis, to help, for example distinguish between the recurrent, severe, unilateral headaches lasting up to 3 days with nausea that typify migraines and the recurrent, severe, unilateral headaches with a watering eye that can last for a few weeks, that typify cluster headaches. I remember vividly a lecture from a distinguished neurologist who explained that we could diagnose headaches by watching him listen to a patient’s history. Listening to a patient describe a ‘feature-full’ migraine, he would be alert and interested, but listening to a patient describe an equally disabling, but ‘feature-less’ chronic tension headache, the neurologist would look bored and distracted. Doctors often loose interest once they’ve got the information they want.

We are taught to take a clinical history by listening selectively to our patient’s stories to remove the particular, subjective features, which are deemed irrelevant to the diagnostic science of medicine.

I learned early in my life that a pain is almost never just a pain. The ripples spread from the nervous system into the sufferer’s whole life. If you stub your toe or burn your finger, it hurts but it’s quickly over. Anything more complicated – and especially the kind of pain that is recurring or chronic – impacts on the patient’s personality and relationship with the world. Pain does not happen in a laboratory. It happens to an individual, and there is a cultural context that informs the individual’s experience’. What a pain is, and whether it matters, is not just a medical question. Hilary Mantel

Philosopher Havi Carel uses the term “epistemic injustice” to explain the gap between what doctors want to know and what patients want them to know. Our refusal to pay due attention and respect to our patients’ account of suffering is a “wrong done to someone specifically in their capacity as knower”. At its core is the “denigrating or downgrading of [patients] testimonies and interpretations which are dismissed as irrelevant, confused, too emotional, unhelpful, or time-consuming”. All of which must (ought to be) be familiar to doctors who have struggled with patients in chronic pain.

Patients give their bodies over to doctors and hospitals only to encounter inattention and indifference, not because they cannot express their suffering, but because their language is unvalued and unrecognized in medical culture.

Doctors are taught to be sceptical of patients’ accounts, treating them as unreliable, insufficiently articulate, and subordinate to their own interpretation. But a degree of scepticism is necessary, not simply because accounts are sometimes inconsistent and inauthentic, but because accounts of suffering serve a multitude of context-dependent purposes and warrant a wide range of responses, for example, not everyone wants sympathy or action.

For patients in chronic pain questions such as, “Why me? Why now? Why does is hurt so much? Why can’t you tell me what’s wrong? Why can’t anyone help?” – and, just as important, their own, tentative answers to those questions – still need acknowledging even if they cannot be answered. When Sharon accused me of not listening to her, the problem was not simply that I was not listening, but that I was listening in the wrong way, I had failed to acknowledge her suffering and she didn’t believe that I believed her. In order to ask the right questions about pain we have to unlearn what we have learned about taking a clinical history; we cannot presume to know about suffering from a clinical history.

The pain with no name

The pain clinic, neurosurgeons and psychologists discharge patients when their course of treatment is over, relieving them of patients for whom “nothing more can be done”: “I am discharging this patient back to your care”, “surgery was not indicated”, “your patient wasn’t suited to the psychological milieu”, “no cause for your patient’s pain was found”, “serious pathology was excluded”. As medicine becomes more specialized and fragmented, it is increasingly common for patients to be discharged back to the GP with the specialist satisfied that their organ of special interest is not responsible for the patient’s symptoms: “non-cardiac chest pain”, “functional abdominal pain”, “referred knee pain”, “mechanical back pain”. Our patients are rarely ever satisfied with the lack of diagnosis and the GP remains to face the patient’s pain and frustration. GPs are the ones who have to care for patients for whom “nothing more can be done” or for whom, “no cause for their pain can be identified”.

On the psychological level recognition means support. As soon as we are ill we fear that our illness is unique. We argue with ourselves and rationalize, but a ghost of the fear remains. And it remains for a very good reason. The illness, as an undefined force, is a potential threat to our very being and we are bound to be highly conscious of the uniqueness of that being. The illness, in other words, shares in our own uniqueness. By fearing its threat, we embrace it and make it specially our own. That is why patients are inordinately relieved when doctors give their complaint a name. The name may mean very little to them; they may understand nothing of what it signifies; but because it has a name it has an independent existence from them. They can now struggle of complain against it. To have a complaint recognized, that is to say defined, limited and depersonalized is to be made stronger. John Berger

Brenda recently joined our practice. “Doctor, I have to tell you, I have cancer and a headache and I’m not worried about the cancer.” It was the first time we had met and I was the first doctor she had seen in years. “I have seen about the cancer on the telly, and I know that a woman of my age shouldn’t have no bleeding and that means it’s cancer and they’re going to do an operation and I’ll be ok.” This is exactly what she said and though it’s unusual that someone is so direct, it serves my point well. “It’s the headache I cannot stand doctor, what is the cause of it?”

Pain we cannot explain is frightening because of what it might be. Even though there is little or no relationship between what we can see from scans of your knees or back and the amount of pain in you’re suffering we make good use of the therapeutic value of explaining your pain in terms of arthritis or a slipped disc. Brain scans are of no use at all for the vast majority of headaches. The resulting anxiety is felt most acutely by patients, but for doctors dealing with headaches, a great deal of the variation in specialist referrals is due to our own inability to cope with uncertainty.

The uncomfortable truth is that most of the time we just don’t know why pain hurts so much.

[Pain is] … a Cartesian dualism by its subdivision into “sensory” and “psychological”. This is an intellectual artifice invented to preserve a concept of divided brain and mind. There is not a scrap of physiological or psychological data to support the dualism. (Wall see Diski / Jean Jackson essay)

In seizing upon simple explanations we contribute to the shame and stigma felt by people suffering chronic pain. Faced with chronic pain from undiagnosed endometriosis, author Hilary Mantel experienced this:

I was aware that my condition was exacerbated by stress, and I knew that if I confessed to this, stress would be blamed for everything … besides, every visit to every doctor would begin with a lecture about my weight.

The loneliness of pain

I think therefore I am in pain quickly becomes I think therefore I am alone. Jenny Diski

“I’ve had this since university, but none of my friends know about it.” Toby, a 27 year-old accountant looked fit, athletic and confident. He was asked to attend the surgery because everyone on our list with inflammatory arthritis has to be assessed for his or her cardiovascular risk factors. He has arthritis in his left knee. “Do you think I’ll ever be able to play tennis again?” he asked me. This was yet another ten-minute consultation that extended well beyond its brief and timeframe. The last time he played tennis was at university, six years ago. “There are weeks when I don’t see anyone except at work, I can’t stand in a bar, dance in a club, or even walk anywhere. I don’t want anyone to see me when I’m like that.” “So what do you do?” I asked, “Nothing”, “Nothing?” “I just stay at home watching TV, I don’t even answer the phone, I don’t want to have to explain or make excuses. After a while, people stop asking.”

“Since you ask, I do still get headaches, almost every day,” I interviewed my wife for this essay. “Rarely a day goes past without a headache. They’re horrendous, they’re from the back of my neck to the top of my head, they’re exhausting. If I work for a day, they’re twice as bad for the next three days. I love to swim, but twenty minutes of swimming brings on a migraine – once a week I can just about bear it, but I can hardly speak for most of the rest of the day. They make me feel irritable which I hate, so I avoid people until they settle down. They’ve been like this for years; I’ve seen GPs, neurologists, physiotherapists, massage therapists and a psychiatrist. I’ve had acupuncture and done yoga, but they’re no different now from how they were 15 years ago, and I expect they’ll be the same in another 15 years.”

People with chronic pain grow tired of telling the same story over again. There is none of the drama of cancer or an attack as in heart, gout or the runs. Chronic pain is dull and exhausting. Most of my patients with chronic pain are tired of making excuses, trying to explain why they cannot join in or help out. ‘No-one gets flowers for chronic pain’, most suffering goes on without witnesses.

(Pain) shows us, too, how those around us

do not, and cannot, share

our being: though men talk animatedly

and challenge silence with laughter

and women bring their engendering smiles

and eyes of famous mercy,

these kind things slide away

like rain beating on a filthy window

when pain interposes. John Updike (quoted in Leder)

Doctors are uneasy about spending time with the lonely. In an age of ever increasing demands for healthcare productivity, where the heavy hand of state surveillance scrutinizes the details of every clinical encounter, doctors feel increasingly anxious about consultations spent listing, bearing witness to suffering or providing comfort instead of diagnosing and treating, measuring vital statistics or giving lifestyle advice, all of which are recorded measured and paid for. How close I came to sticking to the cardiovascular risk-factor script when Toby came in, but how much more I learned by discovering about his isolation, his fears and his experience of chronic pain. It’s a tragedy of modern healthcare that we spend so much time with people who feel perfectly healthy, yet have risk-factors for disease such as raised blood pressure or cholesterol, and yet have so little time for people who are in pain all the time, but have nothing to show for it and nothing to measure.

Lonely patients are twice as likely to visit their GP, and yet the blogs and other testimonies of people with chronic pain are full of people who have given up going to their GP, often because their GP has given up on them. I know the feeling of despair when Sharon is on my appointment list, “Why does she keep coming back? What can I possibly do?” It is this despair that’s motivated this essay and driven others away.

It is little surprise that patients with chronic pain experience acutely the sense of being unwanted and unwelcome.

Chronic pain patients sufferers typically report experiences of isolation and alienation from their physicians and providers, from their care-givers, and even from their own bodies. … chronic pain sufferers rate the alienation they experience from their physicians as qualitatively worse than alienation from loved ones. Daniel Goldberg

Pain and the body

The healthy body is transparent, taken for granted. This transparency is the hallmark of health and normal function. We do not stop to consider any of its processes because as long as everything is going smoothly, it remains in the background.“The body tries to stay out of the way so that we can get on with our task; it tends to efface itself on its way to its intentional goal.” This does not mean that we have no experience of the body, but rather that the sensations it constantly provides are neutral and tacit. A good example is that of the sensation of clothes against out skin. This sensation is only noticed when we draw attention to it, or when we undress. Havi Carel

Chronic pain is a constant reminder of a broken body. In Kahlo’s self-portrait above, the white straps represent the metal corset she had to wear after she broke her spine in a coach crash as a young woman. They also represent being chained to a broken body – she cannot escape her shattered spine or the nails in her flesh. She is beautiful and sensual, but the biggest nails are over her heart because the pain of love is as real as any other, and her face is brave and stoical and yet tears roll down her cheeks. The land behind her, the context in which she stands is barren and forlorn.

Marian came in with her husband to ask if I could help with his impotence. He looked down at the floor and didn’t seem too keen to join in the consultation. I was prepared for this because we had discussed his problem when he last came in alone. It wasn’t that he was impotent, but that even when they made love as cautiously as possible, his back-pain afterwards was so severe that it was impossible for him to continue waiting tables for the next couple of days and his job, at one of London’s finest restaurants, was on the line. “Everyone who waits tables has back pain”, he explained, “so you don’t talk about it, you certainly don’t complain about it, you just get on with it. And you certainly don’t take time off for it.” Pain’s isolating tendencies have no respect for sexual intimacy.

Conclusions

My motivation for writing this essay came out of despair. My intention was to confront and examine why I felt like that and in my conclusion I will try to articulate what I might be able to do about it.

In her essay, The Art of Doing Nothing, Iona Heath explains that, “in medicine, the art of doing nothing is active, considered, and deliberate. It is an antidote to the pressure to DO and it takes many forms.” Too often when confronted by patients which chronic pain, we “do something” in order to get rid of them, we send them for another investigation or another opinion or we prescribe more drugs. I don’t doubt that this partly explains why the rates of deaths from prescription pain-killers are so high. Another reason for “doing something” is because chronic pain traps us in the present and destroys a sense of progress. “Doing something” sets us in motion again, even if we’re only going round in circles.

“Doing nothing” needs to be qualified, it is far from passive and far from easy. Heath wrote her essay at the end of a long career distinguished by exceptionally deep and considered reflection. Instead of “doing something” we should learn again how to listen, think, acknowledge and bear witness.

Listening to stories about chronic pain makes doctors feel helpless, exhausted, anxious and at a loss for words. Paying close attention we might recognise that this is because the restitution narrative is inadequate and that we are trapped in chaos. I’ve explained how to listen for these different narratives in a recent essay about forgiveness: it’s both a warning and a ray of hope that we might be stuck in chaos for a long time (in the case I discuss, it’s 18 years). Recognising this is in itself a therapeutic opening. As a doctor I must resist the temptation to push toward this opening prematurely. The chaos narrative is already populated with others telling the ill person that “it can’t be that bad”, “there’s always someone worse off”, “don’t give up hope”; and other statements that ill people often hear as allowing those who have nothing to offer feel as if they have offered something.

To deny the living truth of the chaos narrative is to intensify the suffering of whoever lives this narrative. The problem is how to honor the telling of chaos while leaving open a possibility of change; to accept the reality of what is told without accepting its fatalism. Arthur Frank

When Frank wrote his classic book on medical narratives, The Wounded Storyteller in 1995, he wanted to help clinicians listen to their patients. He wanted to show that the stories patients tell make a moral case for doctors to be transformed by bearing witness.

Bearing witness is different from witnessing alone. Any doctor who has felt tired or forlorn after spending time with a patient in chronic pain, understands the burden that we feel when our patients share their suffering. We know that this is hard work, indeed, compassion means ‘to suffer together with’.

Chronic pain blogger Jessica Martin offers us a mantra,

I don’t want you to save me, I want you to stand by my side as I save myself.

The word mantra comes from manas (mind) and tra (liberate). The repetition of a mantra is transformative and this captures very well the transformation that doctors need to undergo to better serve our patients with chronic pain. Finding the right balance of proximity and distance is a challenge. Too close and we project too many of our own feelings on our patients, too far and we have abandoned them.

Proximity demands recognizing that yes, the monster is in the room and that the clinician take a stand with the patient in facing that monster. The first and crucial clinical move is to express the commitment to stay with the patient, to be there to do whatever can be done. It is an enormous defect of health-care organizations that professionals often cannot express this commitment because there are constant territorial disruptions over who stays how long and does what. This structured disruption of continuity of relational care is more than an organization problem; it is a moral failure of health care, deforming who patients and clinicians can be to and for each other. Arthur Frank

Writer Susan Sontag wrote about her experience of suffering as she endured two different types of cancer. She also wrote books about how we respond to images of suffering. She clearly wants her writing to give access to what is real, to create knowledge and the conditions for compassionate understanding and ethical action. Indeed, the project of many of Sontag’s best known, early essays is to protect reality from the distorting influence of representation. She wants her essays to affect and change minds and culture (see Ann Jurecic).

Frank’s final narrative is the quest. For the last two months while researching this essay I’ve been swimming in narratives of chronic pain. The chaos narrative is one that cannot be told and so it is perhaps little surprise that they are hard to find. When the story finally can be told, it is the quest. Jessica Martin’s excellent blog, ‘No-one gets flowers for chronic pain‘ is a great example.

Quest stories carry the unavoidable message that the restitution narrative will, one day, prove inadequate. Quest stories are about being forced to accept life unconditionally; finding a grateful life in conditions that the previously healthy self would have considered unacceptable.

Lastly, taking care of patients suffering chronic pain is one of the hardest things I do as a GP. It’s been my experience that patients quite frequently realise this too.

My other concern is with the doctors and nurses who have to deal with patients who are in pain. I think it must be a depressing and unsettling business, unless you are well-trained and supported. Sometimes medics seem callous, and I often wonder if they are frozen because they are afraid. People who are suffering often have an aura of unapproachability. They are cut off, turned inward, preoccupied with their inner experience. Pain requires a kind of concentration, and it’s easy to feel helpless and useless in the face of the patient’s otherness. What healers need to do is muster their own resources of personality and professional knowledge and address the fear as well as the pain: to provide reasoned reassurance, information, and above all, hope. Hilary Mantel

Hilary Mantel quotes © Copyright 2013 International Association for the Study of Pain. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

References and further reading

Pain is weird. Fantastic overview from Paul Ingraham – Painscience.com

The Buddhist practice of Tonglen uses things we find difficult to “wake up” instead of being a big obstacle. We learn patience, compassion etc. from people who push our buttons. “The job of the spiritual friend is to insult you … you need people around to provoke you so you know what you need to do.” It has been very useful in thinking about how I manage patients with chronic pain. The key is to engage with the difficult emotions and find better ways to cope rather than avoiding them.

No-one gets flowers for chronic pain. Great chronic pain blog demonstrating narrative as quest.

How to understand someone with chronic pain. Good advice via Wikihow

Spoon theory: A simple way to explain chronic pain to others

Body of work. An author, Barbara Gowdy – who lives and writes with, but not about, chronic pain

The Lived Experiences of Chronic Pain. Daniel Goldberg 2012

Asking the right question about pain: Narrative and Phronesis. Arthur Frank 2004

Illness as Narrative. Ann Jurecic 2012

Stigma, Liminality and chronic pain: Mind-body borderlands. Jean Jackson American Ethnologist 2005

Mantel_IASPInsightJune2013 copy © Copyright 2013 International Association for the Study of Pain. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

How doctors respond to patients’ shame.

The Compassionate Brain: Humans Detect Intensity of Pain from Another’s Face http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/content/17/1/230.full

Pain: Science, Medicine, History, Culture. Wellcome Collection.

Why is is so difficult to find better methods of chronic pain management? This ain’t livin’ blog

Living with Chronic Pain. Indepenedent 2013

To just be a person and not a patient any more. Heart Sisters blog

Pain really is in the mind, but not the way you think. The Conversation

How Chronic Pain has made me happier. Robert Heaton

Agency without mastery, Chronic Pain and Posthuman writing

Chronic low back pain, self management from Saveyourself

http://www.scoop.it/t/chronic-pain-and-occupational-therapy

Chronic regional pain syndrome

Psychological therapies for chronic pain: very modest benefits

Psychological therapy for adults with longstanding distressing pain and disability – See more at: http://summaries.cochrane.org/CD007407/psychological-therapy-for-adults-with-longstanding-distressing-pain-and-disability#sthash.Se27mPZK.dpuf

The best evidence strongly indicates that these stuctural findings on X-Ray and MRI are not clearly related to the onset, severity, duration or prognosis of low back pain http://www.bodyinmind.org/spinal-mri-and-back-pain/

Healthtalk online: Videos of patients discussing life with chronic pain: http://www.healthtalkonline.org/chronichealthissues/Chronic_Pain

Havi Carel epistemic injustice: via Kings Fund

“The placebo effect is the effect of everything surrounding the fake pill, or the real pill,” he says. “It’s the compassion, trust, and care. It’s the ritual and symbols. It’s the doctor-patient interaction.” http://www.fastcoexist.com/3016012/the-placebo-effect-is-real-now-doctors-just-have-to-work-out-how-to-use-it

Jenny Diski: Feel the burn. LRB

Pain Toolkit. Resources for living with chronic pain. Excellent UK website

Living With Arthritis

Pain. Is it all in your mind?

Understanding pain in 5 minutes

Thank you so much for this. I once had a doctor that was seemingly irritated by my miserable chronic pain and exhaustion, and withheld a diagnosis of fibromyaliga/cfs made by a physiotherapist, denying me any possibility of understanding and dealing with my condition. I left his practice, and found a doctor who, when I try to explain my experiences, can relate them exactly. Speak for me. You cannot imagine what a relief that is – to have someone who can relate to your struggles. Then we get on with the business of planning my strategies for coping. Apart from diagnostics to exclude MS, I have never seen a specialist. I have suffered from debilitating cycles of intense illness and pain for 13 years, but found the courage to chuck in a job that was destroying me and volunteer in Africa, my dream of 27 years, in the full knowledge that I will never get better.

Frida Kahlo found dignity in pain, and so can many of us.

Thanks so much for your comment. It’s very hard for doctors to admit we’ve failed our patients, and it was very hard to write this post, but knowing how acknowledgement and understanding can really make a difference will surely help us.

This is so, so tender, true and lovely. I read it through two lenses: as the mom of one child with debilitating chronic pain and of another who is just starting medical school. I find myself responding in a “motherly” fashion to you. I think mothers of children with chronic pain share a feeling with our children’s physicians that it’s our job to DO something to fix it. You’re supposed to find the cause and treatment; I’m supposed to find the right doctor who will find the cause and treatment. And we’re both failures in our respective roles if it can’t be fixed. Perhaps this also affects siblings, as my son will be going into medical research.

For years, we had the same experience you describe of being referred out to specialists with test results on the specialists’ organs/systems coming back negative and then being referred back to our family doc. We lived in a small town during the early years of my child’s illness and our family physician was the only doc in town who would deal with chronic pain patients. I developed so much sympathy for him. And so much respect. Like you, he experienced despair, demonstrated deep compassion, was stoic and loving in the face of my early “why can’t you DO something!!” outbursts, and persisted in always reading the recent research and seeking new treatment options. As thankless, difficult and exhausting as his chronic pain patients could be, he had a big soul with the capacity to bear witness and hold out hope. I am so touched by your ability to articulate what it was he was able to do for us and so encouraged that you see it.

You mention tonglen, so I want to point you to resource I don’t see listed here (I haven’t gone back yet to read earlier posts, so perhaps you’re already aware of her). Toni Bernhard is a patient with a very debilitating illness who has written two wonderful books about applying Buddhist principles/practice. Her first is “How to be Sick” and her most recent is “How to Wake Up.” She also writes for Psychology Today. I think you, and perhaps some of your patients, would value her work.

Thanks for this searing exploration of the physician’s side of chronic pain. Good for you. And, hugs.

Thank you so much for this beautifully worded and extremely thoughtful essay. “No one gets flowers for chronic pain” is such a great quote. It reminds me of what my friend and colleague Dr Louise Stone says (she has done a PhD on the clinical reasoning of GP novices and experts when patients present with mixed emotional and physical symptoms) … “There are no fun runs for medically unexplained symptoms”

Twitter @drgenevieve

http://www.genevieveyates.com

Another superb post, struggling with the difficult questions and finding meaning where there are no pat answers. I’m reminded of something I read recently from The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat: “To restore the human subject at the centre — the suffering, afflicted, fighting, human subject — we must deepen a case history to a narrative or a tale; only then do we have a ‘who’ as well as a ‘what’, a real person, a patient, in relation to disease.” This is what you do — bear witness to the real person in the suffering patient.

Hi Jonathan! I’m now working back in the NHS as the lead nurse in a major pain service and I’m going to share this with our entire team so that they can have an understanding of what you, the frontline GP, goes through every day with chronic pain patients. Thank you for sharing this. Regards, Kathryn

Well done. This really captures the mutual dissatisfaction in the Dr-patient relationship where mere language and the context of our encounters is insufficient to convey the true nature of suffering. It limits the Drs ability to shift from physician to healer and undermines releasing the inner healer within the sufferer. We need whole new models of care in which to approach these transactions.

Thank you for this.I have chronic pain due to arachnoiditis and arthritis. One interesting thing is that when you do have a diagnosis, is that every symptom you experience is put down to that diagnosis, and any new pain is dismissed. I was going backwards and forwards to my GP with pain which was new, and dismissed with ‘what do you expect me to do?’

I eventually found a neurosurgeon on my own, discovered I had spinal stenosis and ended up having 2 laminectomies.

I was so demoralised after any visit to my GP that I no longer go.For anything.

And yes, pain is lonely.

Wow. Speechless. One of the best things I’ve read. And if you substitute chronic pain with chronic disease or disability, it’s still all true. Although I fully respect the foundation that pain is invisible and therefore much harder to grasp and both validate and “treat”.

Just wow. Kudos. Well done. And thank you!

I am moved beyond words. You have stepped with care and courage into the territory of our common humanity – our human-ness and our human-mess. Blessings.

Thank you, thank you, thank you.

As an ‘academic’ and EBM person I have seen the difficulties clinicians have had in navigating the patient pathway and knowing what to do with me. As a patient I have spent the last 12 years dealing with acute and chronic pain and neuropathy as a result of severe disc and vertebral degeneration in my lumbar spine. I consider myself fortunate in having a ’cause’ or ‘reason’ for my chronic pain identified. Following two fusion surgeries I was reclassified as having ‘failed back surgery syndrome’ (a term that I hate as in principle it didn’t fail in enabling me to walk again it just failed to remove all the pain and all the neurological deficit that was the result of long term nerve compression). I was also lucky to have a great pain management team which led to the implantation of a spinal column stimulator to work on some of the neuropathic problems. It doesn’t rid me of my pain but helps me to manage it better.

Living with pain is a daily battle and one that is very difficult for anyone to understand. I, like many pain sufferers, am bored of talking about my back or explaining why I’m still in pain and why I can’t do what my peers do or would like me to do. The result: I don’t talk about it or I play the ‘life’s shit sometimes but you have to get on with it’ card. My decision to internalise my feelings is based on my desire to regain my former life and to maintain my own mental health. Of course it doesn’t work but I feel often it is easier not to talk about it than to dwell on it. At 37 I have spent much of the last 12 years struggling with pain, the last 6 of which have seen me ‘disappear’ from the lives of many of my friends and colleagues as I struggle to navigate my changing life and identity. The challenge for clinicians is to accept that those individuals with long term/chronic pain have to manage their pain while grieving for their previous lifestyles and identities. This is not something that can be ‘fixed’ or dealt with in a 10 minute appointment.

I hope your essay will be read far and wide to enable all clinicians to be honest about their difficulties (and shortcomings) when working with patients with chronic pain.

Dear Ceri,

Thanks very much for sharing your experiences. I hope when I write what are increasingly ‘confessional’ essays, that a space is opened up like this and it’s very touching when this happens. I’ve been swimming in the waters of this blog for at least the last 8 weeks and sharing ideas with some close friends. In that time I’ve realised how important it is to keep sharing our doubts and fears if we want to be compassionate, resourceful and resilient practitioners. I hope we meet someday soon, Jonathon

As usual, you have outdone yourself. Brava!

Reblogged this on Contemplations on Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and commented:

This is a long article…insightful, lovely, and challenging. I suggest diving in.

Reblogged this on ladybirdabroad: one year with agricultural and cocoa growing communities in Ghana and commented:

I had to reblog this, and I hope that this most excellent, sensitive and honest essay bu a British doctor speaks others as it spoke to me. We all struggle with chronic pain, suffers and general practitioners alike, We need a lot more of this honesty, while the search to understand the lives of chronic pain sufferers, and the causes and treatments for illnesses like fibromyalgia/CFS/ME continues.

Frida Khalo’s painting is shocking, but dignified. We can all find some dignity in pain despite the loneliness and the bleak days.

While we want to only imagine ourselves as saviors of one sort of another, intractable problems bring us back to our human dimensions. They are the solar heat that melts the wax of the wings Dedalus has made for us which causes us to plummet back to earth. While it is best to simply do the best we can under very trying circumstances, false idols goad us to aspire to super competence at all times. When someone comes with problems that cannot be solved at least not easily, we tend to panic or place them in the category of ‘not quite sane and reasonable’ or ontologically blighted. A path out of this impasse is to openly acknowledge our limits to effect positive change and combine that with a statement of willingness to accompany them as witness and confidant part of the way on their path.

As always, Jonathan, your willingness to explore and write about these difficult issue is greatly appreciated.

“We are here to help each other to get through this thing, whatever it is.”

-Mark Vonnegut

Thanks very much Duncan, I love the Vonnegut quote. Perhaps under-explored, and a subject for the next blog perhaps is the fear that doctors have that by staying with their patients whilst ‘doing nothing’ we are not so much standing besides them as standing in the way of their progress and independence. A theme that has emerged in talking with physicians is how, with the best will in the world, our patients in chronic pain end up on medication which escalates until it feels completely excessive and somehow out of our control. Whilst there is negligent prescribing, I suspect those negligent prescribers don’t agonise and I wonder whether the difference comes down to how much we worry about what we’re doing?

Goodness me. I have been waiting to find time over the last 24 hrs to get the opportunity to sit and read this and I am not disappointed.There is something for everyone here-but for me as a physician, a fellow GP, there is a wealth of help, support and ideas.

I can only thank you for taking the time to produce this-I am sure many doctors, and in turn many patients, will benefit from your efforts.

Explore the narrative, avoid the chaos.Now there is the challenge.

Many thanks,

Richard

Thanks Richard, I’ve been swimming in these narrative waters for a long while now, and it is getting easier, but it’s not so much an epiphany as something that takes regular practice and a good set of trusted peers to keep going … which is why the blog starts and finishes the way it does. Thanks for taking the time to read it, it took about 8 weeks of reading and thinking to get it together.

Hello, again (as with previous comments) appreciation for your writing and your work. I’m doing a PhD on the experience of doing chronic conditions work; and would like to read the Hilary Mantel you quote from in full. Are they all from the same source, and is it her memoir? The link is to International Assoc for Study of Pain which seems incorrect?

Cheers,

Anna (Tasmania, Australia)

The article was from the latest IASP insight magazine with is available to IASP members. The other links at the end of the essay are mostly open access,

thanks, i’ll seek access through them then.

I’ve now added links to the original Hilary Mantel essay. It’s © Copyright 2013 International Association for the Study of Pain. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved.

Thank you for this beautiful, moving essay which speaks to the heart of the matter of chronic pain.

Wow! I cried throughout the whole thing! I’ve been in chronic pain for 13 years. I first experienced this “life-changing” pain when I was 20 years old and pregnant with my only child. This is dead-on and so eloquently written! Thank you!

I went on to read your post about forgiveness from here, and commented on that thread. Really, please, keep this going.

In my experience, it takes a special person who suffers with chronic pain to live in a society who disrespects the weak and handicapped. Especially a disease that is invisible to the eye.

You are at peace with this narrative?

So you are advocating for patients to live with the failures of modern medicine?

Is this a statement of a physician surrendering, because it is too hard to heal assist these patients out of their despair?

Are you just perfecting your prose and writing skills?

I am not offended, but deeply disappointed that the suffering are losing allies. I hope I am reading into this with the wrong conclusion.

Thank you for a fabulous post. A few thoughts from a RN who has chronic pain and who, as a nurse community case manager for frail low income seniors counsels on it a lot:

Chronic pain is an incredibly tangled web of original trauma, immobility and splinting, anxiety and tension, altered rest and altered hormonal patterns, eventually a hyper-sensitized central nervous system…it it no wonder that it becomes incredibly frustrating for the person who “has” it plus family and health care providers.

Optimally any approach is going to have to include several modalities and digging deeper than most doctors are trained to understand – for the usual “be more active” won’t help much if there isn’t a referral to someone who can help the person learn to really feel the area AND the area around it and to open/soften the splinted areas (which may be pretty far from the pain – for instance, for knee, the contralateral hip may be holding a ton of stuff that makes mobilizing for activity hard)

Also, how one approaches the chronic pain itself. When I work with people I talk about how it is common to try to isolate it so it stands apart from you. It becomes like this big ogre shuffling alongside you all the time. Unfortunately, making it The Other just feeds it more power – like in aikido, the more you oppose your partner, the more you give him power over you. So there needs to be a way to accept the fact of the pain as a part of you – not defining you, but integrating into part of you – that makes it easier to not fight it and find other ways of coping like distraction, breathing and relaxation, etc.

Last thing I’ll say is that while for some people opiates are over-used and can make it harder to find the modalities for breaking the chronic pain cycle, for many others they are really important tools that allow for activity and for participation in daily life, so there is no more point in being judgmental about opiates than there is in being judgmental about heart meds: if it is the wrong med or the wrong dose, change it but if it is working well as part of a total approach let it be.

This is difficult and draining to have patients who have problems that we are having difficulty or cannot help. I agree with the statement “The first and crucial clinical move is to express the commitment to stay with the patient, to be there to do whatever can be done. “]

When Frank wrote his classic book on medical narratives, The Wounded Storyteller in 1995, he wanted to help clinicians listen to their patients. He wanted to show that the stories patients tell make a moral case for doctors to be transformed by bearing witness.

I feel most doctors do try to listen and are concerned about the wellbeing of their patient and how to help them. Healers need to keep themselves healed so they are able to continue to provide optimal healing for their patients. What healers need to do is muster their own resources of personality and professional knowledge and address the fear as well as the pain: to provide reasoned reassurance, information, and above all, hope. Hilary Mantel

It is lonely and sad and isolating feeling overwhelmed with the disfunctional medical system as we are trying to do the best we can with what resources we have to help our patients. we need to support one another so we are better able to help our patients.

This is a very powerful piece, thank you. I wish more doctors (GPs and specialists) would let patients help them through the chaos. I have been in pain my whole life, and I have always been careful to be constructive and specific with doctors. I never ask what is wrong with me, I always ask what can be done to reduce my suffering.

If I am too specific with suggestions, they bristle and shut down because it’s the doctor’s role to come up with solutions. If I make open ended requests for support, they can’t think of anything because they haven’t looked into the practicalities of how pain can be managed. Diagnosis is all they seem to be interested in. It’s enormously frustrating. I always ask to be referred to physio because physiotherapists are often brilliant at coming up with practical ideas to reduce suffering. Why can’t more doctors do this? Surely it would increase their satisfaction to know that they have helped someone? It feels sometimes like being a doctor is all about getting the crossword-puzzle hit of diagnosis.

This morning I had a very helpful meeting with the excellent physiotherapists, anaesthetist and psychologists running our local pain service. I think phsyios and psychologists often have the time, expertise and understanding that patients need and doctors sadly lack.

As someone determined to THRIVE with chronic pain from fibromyalgia, several spinal conditions, congenital hip dysplasia, and patellar femoralis syndrome and as someone who lives to help others THRIVE too, thank you for this post. When it is chronic, there just has to be something more than just pain. When you know it is never going to go away, you have to find what else there may be for you. I refuse to be an angry bitch because of pain. It is not my style. Pain means change and I am capable of change. I can learn new things. I can accept a new normal. I can embrace my life and my pain and create something new with it. I am worth the effort. I can even be compassionate with my doctor when he’s being an idiot about it. But for the internist who simultaneously refused to release me for full-time work because my pain was intractable while refusing to complete the examination paperwork required for disability and social services, I can (and did) fire him and report him to the state and his contracted hospital. I can and do hold myself and my physicians responsible for my care. As for me, I am not afraid of the pain of figuring out what works for me. In so doing, I have learned in my disability I have capability I never realized. Incurable pain brings creative solutions. If you are in pain or you care for someone in pain, please do not give up or allow someone to give up. Embrace the positive and move forward even if you have to drag that pain along for the ride. THRIVE!!!!!!!!

This article is yelling out, “I must grieve, I have surrendered to the pain because I have no more options!”

You call this a quest narrative related to pain and suffering and we as providers should force patients into victims to accept this miserable fate. Please NO! This is not what we are in the business of doing. We need to give these patients, providers and the rest of the medical community the education and wisdom of every option in our arsenals.

Every day pain is a part of humanity, but chronic unresolved, undertreated and mistreated pain is new in the past few decades. I would like the resolution part of this narrative to also be presented here as well for those who are not spent, exhausted, satisfied and ready to give up and grieve.

The resolution narrative should inspire some to be proactive with chronic pain therapy. The resolution part as it relates to Therapy has been marginalized and discounted. For the past 2 decades medicine has relied too heavily on technology to fix pain. Fixing pain is a misguided concept that must be discarded from our beliefs. Fixing pain is a notion that starts out with a false paradigms that a natural joint is weak, feeble, incapable of lasting a lifetime and that our technology and artificial structures are much better than nature.

HOPE and HELP is our primary responsibility as frontline caregivers. We are public servants and it is our job to treat the suffering with all available options. We should not be in the job of acquiescing to this scourge of chronic pain. We must resurrect the therapies of antiquity, which were used to treat the builders of the pyramids, Stonehenge and the temples in the Andes. They had to have used their bare hands as instruments of healing. Touching patients with hands-on therapies would be vital to the future of medicine.

The main focus of therapy should be aimed at myofascial tissues. Janet G. Travell, MD and David Simons, MD are the myofascial pain gurus, who went so far as to say that “chronic pain IS myofascial and thus treatable until proven otherwise.” The only way to disprove it to began the therapy and see the results.

What is Therapy or forms of myofascial release therapy?

Hot Epsoms Salts soaking.

Get on the floor or bed and start stretching.

Get more magnesium in the diet.

Get a foam roller to work on your hip/back and abdominal area.

Use self-trigger point release or acupuncture with your hands or a T-cane.

Find a P.T. specialist who can perform “Spray and Stretch.” Get help from a massager professional.

Get help from an Acupuncture professional.

Ask to be taught D0-It-Yourself dry needling.

Find a graduate of Gunn IMS, (Intramuscular Stimulation).

Find a trigger point specialist who knows Janet G. Travell, MD or Edward Rachlin, MD

You must treat the entire body from head to feet.

Here is a list of the authors of past and present day who are the primary source for myofascial pain therapy.

>Intramuscular Stimulation using the techniques of C. Chan Gunn, MD.

>Trigger Point Injections using the techniques of Janet G, Travell, MD, David Simmons, MD and Edward Rachlin, MD.

>Ligament and tendon relaxation techniques of George Stuart Hackett, MD.

>CraigPENS as per William F Craig, M.D.

>Myofascial Release by Gokavi, Cynthia N. Gokavi, MBBS.

>The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook: Your Self-Treatment Guide for Pain Relief, Second Edition by Clair Davies, Amber Davies and David G. Simons (Aug 1, 2004)

>Fibromyalgia and Chronic Myofascial Pain: A Survival Manual (2nd Edition) by Devin J. Starlanyl and Mary Ellen Copeland (Jun 30, 2001)

>Advanced Soft Tissue Techniques as per Leon Chaitow, ND, DO

>Medical Acupuncture as per French Energetic protocols of Joseph Helms, MD.

Interesting – I hadn’t realised these treatments were termed myofascial. Over years of personal trial and error I’ve found many have worked for me. But I think this article is about the doctor’s despair, more than the patient’s. It’s important to recognise how important this issue is: if a doctor hopes for full resolution of pain, or full explanation of symptoms, they will shrink from patients for whom this is impossible. Doctors need to be pushed to think about what motivates them, and where this conflicts with what patients actually need to live a positive life. This article does so brilliantly; I hope many doctors read it.

Afterthought – your post and others made me think, ‘Yes! Chronic pain often has a clear set of explanations, even if these are not linked to specific disease.’ GPs (in the UK, at any rate), don’t seem to be able to communicate to patients how the central nervous system gets skewed when it’s been under strain. For many patients, a simple explanation of that would be enough. The physio who changed my life told me, ‘it’s like a burglar alarm that gets louder if nobody comes’. That simple phrase was enough to stop me panicking, and to start to take control of my pain. In many cases, nobody is going to come and reset the burglar alarm, because there are too many knock-on effects continually setting it off. I don’t think this is hard for people to understand, and it does give people a causal understanding of their pain, even if it’s not precise enough for most doctors. Perhaps one of the issues with chronic pain is that ‘tell me what’s wrong with me’ is understood in different ways by patients and doctors.

I find it extraordinarily difficult to explain chronic pain (and most back pain) in ways that make sense to the patient and are, to the best of my knowledge, true. Patients find it extraordinarily to explain chronic pain to doctors in ways that make sense as well. We’re in a double bind of having to explain something for which experience rather than cause is the best we can do. I found this guide to help people understand chronic pain yesterday which might help: http://m.wikihow.com/Understand-Someone-With-Chronic-Pain

You might find this interesting: The Horse Is Dead: Let Myofascial Pain Syndrome Rest in Peace http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00453.x/abstract

Hello, Jonathan — magnificent. I am writing a book about the back pain industry. You might have a look at my website. I’d like to interview you for a chapter about how GPs feel about managing patients with chronic low back pain. I hope you will get in touch soon. Thank you for this stunning work.

Cathryn

I’m happy to help. I’ve not researched how GPs feel, nor am I aware of any research either, though I don’t doubt I’m alone!

there is a bit of GP experiential stuff about practice in general, although i’m not aware of anything specific to how GPs feel about pain management. Would be interested to be referred to any literature you’ve come across. Am writing about how health professionals feel about ‘doing chronic conditions work’, including work with people with chronic pain – anna.spinaze@utas.edu.au

Hi Jonathan, I teach a postgraduate programme in pain management at University of Otago, New Zealand, and I’d love to share this post with all my students. At least half of them are medical practitioners, while the rest are allied health. This essay touches at the heart of why some doctors (and other health providers) continue to try unhelpful investigations and treatments, and why so many people with pain cycle through a merry-go-round of hope and despair as each treatment is offered then fails to deliver.

Interestingly, I’ve just completed my PhD thesis looking at people who cope well with their pain – and every single one of them were helped enormously by hearing “this is how it is”. Without hearing that, they continue to hope there is something out there to help them return to normal. It’s not possible to move forward while holding on to the hope that it’ll be possible to go back to what has been.

I also teach fifth year medical students, and asked them what they had been taught about telling people “you have a health problem we can’t abolish”. While they had been taught about how to break the news of terminal cancer or COPD or rheumatoid arthritis, no-one had broached the topic of how to explain to patients that their pain is persistent and there is no medical answer as to why you have it, nor how to get rid of it. That’s tragic, I think.

Anyway, I’d love to be able to use a copy of this post in my teaching, and hope you’ll give permission for me to download it and pass it on.

kind regards

Bronnie

I’d be honoured and delighted for you to share it, thanks Bonnie

The first words of my current general practitioner, the one I found after the last one told me “you just have to get up and go to work on a Monday morning” when I was in the throes of a massive fibromyalgia flare, were “I’ll take you on as long as you realise I can’t cure you.” Yesssss. That worked for me! Now we when I go to the GP (not that often for the fibro or pain) we focus on coping strategies, often following a sympathetic hearing out and intelligent discussion. The ONLY time I said I could no longer cope prompted a switch to a new regime of medication that has meant I have been able to come to Africa for a year’s volunteering.

thank you, so much, for this. I constantly hope that autoimmune disorders will be more properly researched and understood, but in the meantime it helps tremendously just to know there are clinicians out there who do understand that they cannot “fix” us, so there must be a place between a cure and just walking away. again, thank you.

Johnathan your article is a work of great insight and prose. And your readers love your work.

Thank you for allow me to post 15 yrs of experience using MF protocols to help a couple thousand of my patients. These protocols will not only help providers truthfully and honestly address complex pain. Also the proactive info will give patients have the tools to help themselves which will minimize the fear and thus mental trauma associated with pain.

Are you advocating that modern medicine can’t help those who suffer in chronic pain thus as a community of public servants in medicine we should tell our patients to, “get over it?”

Are you saying that the Cohen-Quintner’s article can usurp countless years of verifiable 1 to 1 positive clinical outcomes?

This blog is about my experiences of caring for patients with chronic pain and the narratives of those who have suffered. You’ve chosen to use it as a platform to promote your own methods. There are many other types of chronic pain including headaches, pelvic, visceral, neuropathic, malignant etc. etc. Whilst readers are welcome to share their experiences, I really think you’ve missed the point, respectfully, Jonathon

I hope you get this published if you haven’t already so that as many medical professionals as possible can access this. As a Psychologist and a chronic pain sufferer, your article brought me to tears. It was so well written, researched, and thoughtful. Your patients are lucky to have you!!

That’s very kind of you. I did work pretty hard to figure out how to put this into words, and in the short time since I’ve written it, it really has transformed my experience of caring for patients with chronic pain. I’m really not sure how to go about publication. It’s had over 3000 views online, and I really appreciate the mixed audience and feedback that you don’t get from a journal. If you can suggest anywhere that I ought to try, I’d be very grateful, Jonathon

My agenda is our agenda if we are to succeed in changing health care for the better. I’m just excited to have found the pioneers of pain therapy and wish to share.

“I am Jonathon Tomlinson. … My intent is to show how health is not like any other commodity and that there is evidence to show that it’s bad for health and the economy to treat it like one.”

Actually your statement is exactly why I’m posting. Did you change your intent? The reasons why healthcare is bad and unhealthy is because of a few falsehoods. One of which is discounting Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction. I assumed the blog was about open exchange of insights, discussions, dialogue, education and wisdom.

“I am Jonathon Tomlinson. … As well as criticising present reforms I’ll be adding suggestions for alternative reforms, which are most definitely needed to improve the quality, efficiency and humanity of care in the NHS.”

The beauty of Myofascial disease is that it is easily treated within a holistic social construct. If this issue is not addressed we will falter in our mission.

The next question and I wish you would ask me … “Why do I believe this?”

I will not hold my breath. If you have a complex pain patient and want a few ideas as to how to help them from my experience, just email me.

Thanks you for an audience. Steve aka Dr. Rod.

Steve (aka Dr Rod) I wonder if people with chronic pain (and yes, I have chronic pain too) want to be defined by their diagnosis, or as Tanya (above) points out, they want to THRIVE! There is a difference between having pain and suffering. It’s quite possible to have pain and not suffer – the participants in my research certainly demonstrate this, as do many people who choose to engage with the world and live their lives rather than constantly be ruled by their symptoms.

Suffering is, I think, maintained when we forget that people are all different, their response to pain is different, the effect of pain on their lives is different, and when we respond to their distress by confusing having pain with suffering from pain.

What if, and this is what chronic pain management services are all about, what if we could help people LIVE without suffering, while still experiencing pain?

Yet the focus is so often on finding ways to CURE the pain, yet during the journey to “fix it”, lives are put on hold and relationships can fall apart; the human and economic cost is enormous. If some of the focus on cure was redirected to helping people live with their pain, maybe we’d have fewer people in distress and despair about their pain.

What a brilliant post. There’s some fantastic, insightful advice in this post. Extremely useful for anyone who’s suffering from issues with chronic pain.

Keep up the good work.

Best wishes, Alex

If you have an interests I just have a lecture at a Mayo Clinic seminar on “Enjoying the Management of Chronic Pain”. It has become the most rewarding part of my practice and is not difficult to do. You can take a look at my website, http://www.back-in-control.com to get a feel for the process. It is directed by the patient and is very time-effective. David Hanscom

I want to hug you. I have never read anything so freeing and validating in my 22+ years of living with chronic illness; I am only 37. YOU get it! Thank you.

Thanks Amanda, I’m sending a hug back to you

Reblogged this on seanthum.

It is great to read such a well thought out post and with such true words.

With years of pain behind me in many joints and all medical tests showing nothing I was led to believe it was all in my mind. That patronising smile from consultants when they say there is no clinical reason for the pain.

I finally got to see a physiotherapist, after suffering from Patella Femoral Pain on and off since my teens. In the initial assessment she did the Beighton Scale test… I scored 6/9 and suddenly EVERYTHING made sense. Joint pain, IBS, digestive issues, heart murmur and even anxiety… I had Hypermobility Syndrome/ Elhars Danlos type 3. A rheumatologist confirmed it and now I am being listened to and getting the help I need to get some control over this condition.

A relief indeed.

But if it was all in my head would’ve meant it could go away if I got whatever therapy rids one of ‘all in the head type pain’.

But knowing I have this HMS condition means there is no ‘going away’ with this pain, I have this for life and in a way that is hard to handle as I know I’ll always be getting pain and injuries and it is REAL. I am lucky to have a great GP. But what can she do other than give me pain relief? I do often feel for her and wonder if she ever bangs her head on the desk after I go and see her!

Thank you writing this great blog.

Interesting post shame I didn’t see this last year but then I was still in pain.

I was left in chronic pain for 5 and half years but the 2 conditions I had were completely treatable. In fact when they were finally treated I noticed all the practitioners who listened to me to enable them to be treated where female and qualifed for under 5 years. The male practitioners who heard the begining of my symptoms immediately dismissed me before I finished talking regardless of the length of time they had been qualified. When I got my notes I noticed none of them bothered to put the real reason I came to see them which showed they hadn’t been listening. They put fatigue in when I stated my primary issue was pain. I’m not sure if their response was being sexist, racist or both.

I know from the consultants I talked to and from other stories from women with one of my conditions we are routinely dismissed by primary care practitioners, and called difficult patients. In fact in my case one male doctor threatened to strike me of the practice list if I came to the practice again complaining of my symptoms. (I did but saw a woman who went through my notes and solved that issue.)

I also know from the medical practitioners I’ve met socially that like all members of society they have prejudices against different groups in society however much they claim they do not. My treatment for one of the conditions was different from men I’ve met who had the same condition.

As a result I will now not see any male medical practitioners in general practice.

Pingback: Specialist Back Pain London

What a fabulous piece. I wish I had had a doctor like you years ago. I would have far fewer emotional hangups relating to the patient abuse I have received over the 40 years of my chronic pain.You are in my experience unique and your wisdom is so refreshing. Having just the one person understand for me obliterates the rest who were oh so wrong in their interpretation of my pain as attention seeking/anxiety driven/hypochondria/somatisation/depression etc etc..It makes all the bad things they pinned on me moot.I hope that is the right expression.

Personally I have never expected any GP or consultant to “fix” me.Sadly in the absence of that they have often turned to abuse…there is no other word for it and made me feel worthless and bad for being in inexplicable pain and never recovering. What I needed was some explanation, insight, mutual knowledge and understanding relating to my pain so that I could go away with a direction/tool to be able to manage it myself..It took 15 years for me to get near this. And I had to reach rock bottom first. The best thing one GP ever said to me when he first took me on was “there are some things I do not understand,” At last we were on common ground and it didn’t matter that I had inexplicable and amazing pain or that he could not fix it. Neither of us had failed in any way and that was important. I stuck with that GP for over 25 years until he recently retired.(I went to him after going to another GP in the same practice who had shook me hard and told me there was nothing wrong with me and that I should never darken his door again.) I know that he still does not understand everything about my pain but that is ok because I also know he has done his very best for me. Even when we got it wrong and medications/attempted treatments have made me worse, it was OK, at least we tried. And at times he has gone beyond the call of duty. All credit to him for sitting up half the night with me until the pain injections he gave me took effect and I could sleep. As understanding and acceptance of Fibromyalgia Symdrome has improved over time, I have had access to similar helpful individuals and experienced fewer insultants (my name for consultants who are just rude ) and I am grateful to finally be under the regular care of a knowleadgable, caring and helpful doctor at a pain clinic who cannot fix me but helps and supports me. No longer being a medical pariah is fabulous and absolutely vital to my well being as a person not just as a patient. It is pain relief in itself as I no longer have the pain of being made to feel bad for being in pain. That phrase, no flowers for chronic pain is so true………..so now, when pain flares and all things get worse, instead of feeling bad or staying down, , I just buy myself the biggest bunch of flowers I can find and no longer feel guilty doing so.

Thanks very much for your comment Susan. One thing I have learned, that perhaps only time and experience can teach, is that it is hard to be confident about medicine’s limits, to know where doing more begins to do more harm than good. I’m encouraged that there is growing recognition of this and that it is a countervailing force against the guidelines and psychological factors that force us to do too much and think too little

Jonathon

Jonathon, your descriptions of how the neurologist reacted according to whether or not the headache had “interesting” features reminds me of my experiences sitting in on homoeopathic consultations, and as a doctor.

My dad is a retired GP and homoeopath – he was keen for me to follow in his footsteps as a homoeopath – so I was encouraged to sit in on homoeopathic consultations; and as a child we were frequently treated with homoeopathy. What interested me is that questions that – as a doctor – were of little value to me were very important in deciding which homoeopathic recipe to choose. Yet the answers were very frequently the things that patients would insist on telling me – while I tried to look interested and to politely move them on to something that would help me make my diagnosis and propose a management plan.

I long ago realised that – whatever the value of the homoeopathic remedies (I can see no plausible reason to think they work); the homoeopathic consultation was valuable. The homoeopathic practitioner was keenly interested in the things the patient wanted to tell him; which clearly – probably strongly – enhanced the “doctor as drug” effect. You can’t fake interest. Well, you might be able to try; but I suspect your true feelings will usually (perhaps not always) leak out.

So am I arguing that we should all become homeopaths? Definitely not! But we should learn from what works, and why we think it might work; and in some way CAM practitioners do provide something that patients want that we can learn from. But I don’t know how we can, honestly, transfer this into scientific medicine. It’s one thing to recognise that homeopath’s genuine interest in identifying the right medicine means that they are interested in things that patients want to tell them (where conventional practitioners are much less interested); but it would be dishonest to recommend treatments when we don’t think they work, just because the process of identifying the “right” one has value…

I blogged on this a few years ago: http://peterenglish.blogspot.co.uk/2011/08/do-homeopaths-and-other-cam.html

Pingback: Crip(pl)ing Pain – Poster Presentation at Encountering Pain | The Ladylike Punk

“Brain scans are of no use at all for the vast majority of headaches”

My late wife suffered from a headache for 23 yeas before diagnosing herself. It went away when she laid down and came back when she got up. Karen’s Journal of CSF Leak Headaches and Chronic Pain is now required reading at Duke School of Medicine.

“Karen’s first-hand account of her illness gave an honest, heart-wrenching depiction of what it is like to live with debilitating pain day-to-day.” – The Derrick Newspaper cover story Sept 8th 2014.

Karen could no longer stand the excruciating headache caused by a Intracranial Hypotension, more commonly known as a Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Leaks. A condition that is more common that many think (for example Actor George Clooney had a CSF Leak and considered suicide), yet is so unknown that some doctors argue the condition does not even exist. In the end Karen committed suicide to stop the pain.

An other almost always over looked source of ‘headaches’, a word that fails to describe the actual pain, is Chiari malformation (kee-AH-ree mal-for-MAY-shun). For unknown reasons the number of cases of Chiari are increasing significantly.

Both Chiari and CSF Leaks can be found with the correct scans.

I’ve written more about headaches here https://abetternhs.wordpress.com/2011/11/04/referring/

Hi Jonathon

I am glad to have found your piece; to have further perspective from the other side of the desk, so to speak. As a mature woman with both CRPS / RSD and Lyme Disease, not only do I have severe, unrelenting pain but my condition is extremely hard to address as treatments for one tend to make the other worse…..I am a work-in-progress! In any case, I appreciate your points very much, especially the bit about a crisis of identity. I will continue to post this column on Twitter.

There is, however, one glaring omission in your piece, respectfully: the need for practitioners not just to bear witness but to learn from the patients they treat. Because the experience of pain varies so widely and is so deeply personal, symptom profiles and their developing patterns take time to emerge. Bearing witness will help in identifying these patterns if that is the intent, but endeavoring to learn from these patterns is the driving force behind breakthroughs in research and perspective. Perhaps this is your aim, but I believe we as a society need far more discussion on this. “Bearing witness” is a noble and admirable pursuit for a busy professional but we also need a shift in attitude; health practitioners willing to entertain the notion that people in pain have insight to share from their experiences.

By this I do not mean just that we as patients have insight in to the sorrows and needs of our bodies. I mean that being in pain for a long time teaches you things, about life and about healing and about how our bodies make bids for our attention. While many of these lessons belong with a friend or therapist, some can prove revelatory in the doctor’s office if shared at opportune moments, with a health practitioner who is curious, and genuinely believes that patience and paying attention over time will better enable them to treat those who suffer.

Of course this has no place with patients looking for a cure or a quick fix. If we want practitioners who will advocate for us in this way, we need to be proactive in educating ourselves, and being a partner in our own care. My condition has forced me to do this. As a professional writer, I had a piece published recently in Canada’s Globe & Mail on CRPS, and why I believe it should be studied in the quest to treat pain and neurological dysfunction:

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/health/what-its-like-to-live-with-off-the-charts-chronic-pain/article30467475/

Also, to deal with my own suffering I launched a web site called Pain Maps to help others, and to promote self education and neuroplastic approaches to pain and neurological dysfunction, if I may be permitted to offer this link as well:

http://www.painmaps.com/

Jessica

Thank you so much for sharing this perspective. This will help me in my journey ahead. I will be better prepared at my doctor appointments and more understanding of how my information may be interpreted by a physician. I will try and communicate better so that we can help one another to get myself the best possible treatment.

Very informative. Thank you.

Pingback: Quick fly through mobile apps, assumptions and design | fightingstuff